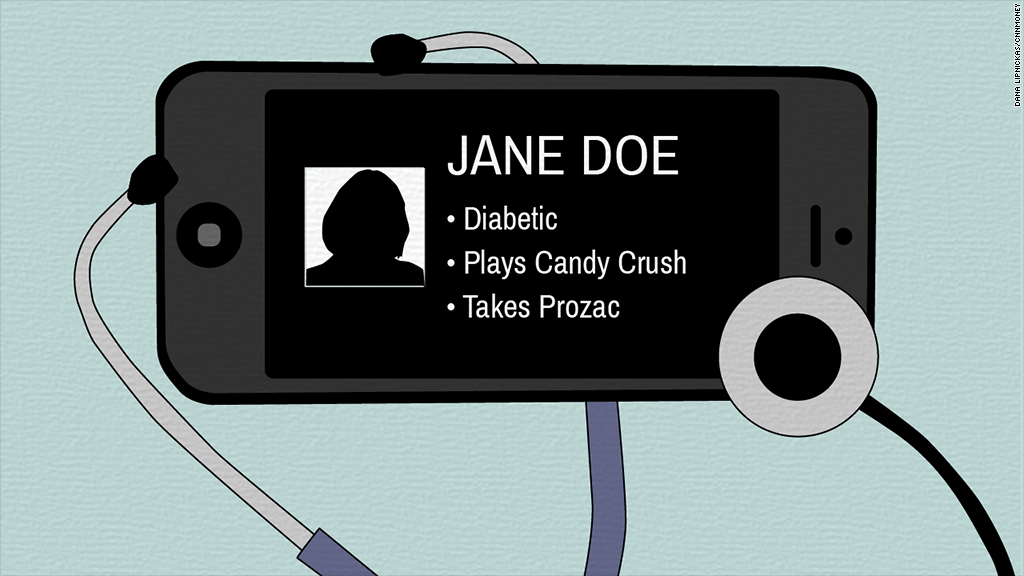

From the diseases you battle to the pills you pop, your most personal health information could be for sale.

That's because some data brokers are collecting information from the surveys you take, websites you visit, products you buy and mobile apps you use to create lists of consumers with certain health issues or medical conditions. They then sell this information to marketers and other companies.

Diabetes, depression, herpes, yeast infections, erectile dysfunction and bed-wetting are just a few of the highly sensitive conditions for which consumer lists are available.

Federal law dictates that this information can't be used to deny anyone for a job or insurance coverage. But with little transparency about who is buying and using these lists, lawmakers and federal regulators say they are worried about other potentially harmful ways the information might be used.

For example, while a "diabetes interest" list could be used by a food manufacturer to offer coupons on sugar-free products, that same list could be used by an insurance company to classify a consumer as higher risk, regulators wrote in a recent Federal Trade Commission report.

Related: How to stop Big Data from getting your health info

Data broker Paramount Lists sells a list of "depression sufferers" who it says can be further targeted based on drugs that they've reported taking, like Zoloft or Prozac. It advertises that these consumers have likely "been encouraged to change their lifestyle habits in the way they live and the products they buy," making them ripe for marketing offers.

Paramount deferred to the Direct Marketing Association, an industry trade group, for comment.

Another company, Great Lakes List Management, hawks a list of households where Alzheimer's patients reside. It says the list could be used by "a pharmaceutical company offering new medications." Great Lakes did not respond to requests for comment.

Many consumers assume that their medical information is protected by strict federal health privacy laws -- called the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA.

However, HIPAA only applies to "covered entities" -- namely your doctor, health plan and any health care clearinghouse that processes your medical or billing information. That means your medical and prescription drug history stored by your doctor or local pharmacy are protected.

Related: Data brokers selling lists of rape victims, AIDS patients

Say you get home from the doctor's and visit several websites to learn more about a diagnosis or register for a website that offers online support. Or you fill out a survey about the medication you're taking in the hopes of landing discounted prescription drugs, or buy over-the-counter products related to your ailment.

All of that information falls outside of HIPAA and can be gathered and sold by data brokers.

Often, the fact that your information could be collected and shared is buried deep in privacy policies, said Pam Dixon, executive director of the World Privacy Forum, a nonprofit advocacy group.

"People who are sick and really need support aren't necessarily thinking privacy. They're just not," she said. "They're thinking I need help."

Related: Big Data is secretly scoring you

The Federal Trade Commission recently recommended that Congress pass a law requiring companies to get "express consent" from consumers when sharing sensitive health information.

The Direct Marketing Association said its ethical guidelines dictate that consumers who are asked to provide their health information should be given "clear notice" that their data will be used by marketers.

And some large data brokers say they have their own internal protections in place. Acxiom, for example, says it already classifies health-related data as "sensitive," and restricts who can purchase the information.

Still, Dixon argues that many companies could make the collection of health data more transparent.

"It's not clear to people at all," she said. "If there was a big sign that said, 'We will sell this information to data brokers,' people would never give it."